One afternoon, while rearranging the studio between sessions with students, I picked up a vase of flowers. Holding the vase in my hands, I slowly rotated it to notice a cluster of freshly cut tree leaves embracing a curved carnation stem—they seemed to be performing a graceful dance together. Fascinating drawing subjects have a way of finding you when you least expect it.

Even though I had a busy schedule that day, this shock of elegant beauty engaged my curiosity. I set the vase aside and attempted to move on to other tasks. But glances of vibrant colors and alluring rhythms of details brought me back to the flower arrangement, forcing me to consider drawing it later that evening.

Author and drawing artist John Berger mused that “each mark you make on the paper is a stepping-stone from which you proceed to the next, until you have crossed your subject as though it were a river, have put it behind you.” I sensed the river could get deep while drawing this complex, flowery subject. Tip-toeing into the water would be my approach.

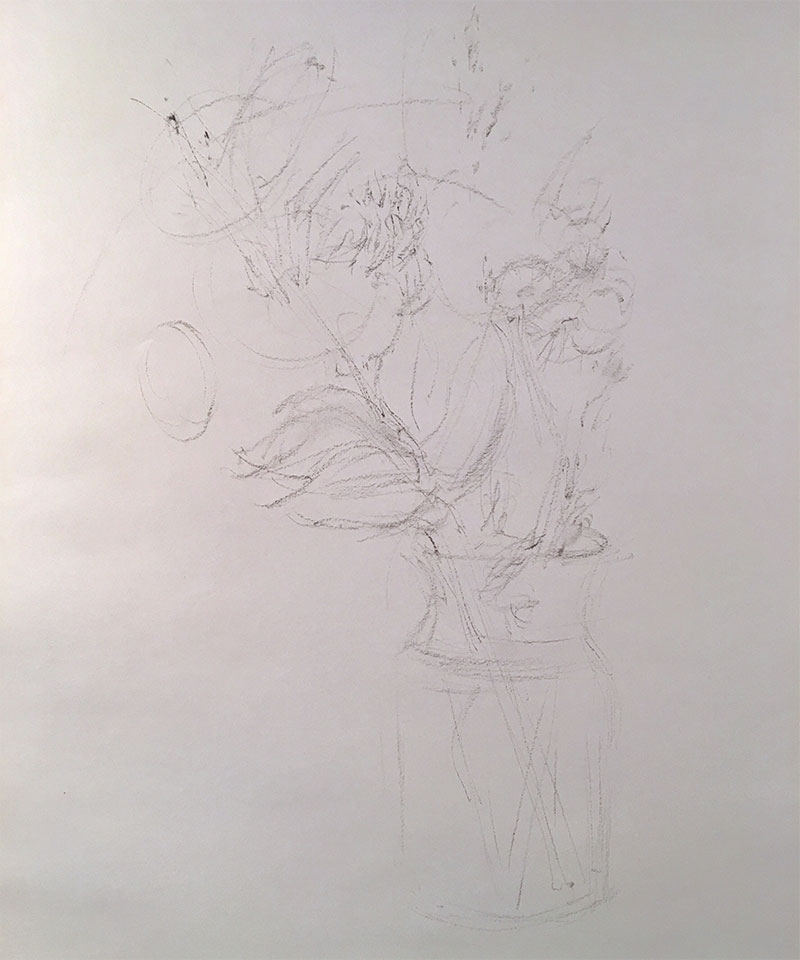

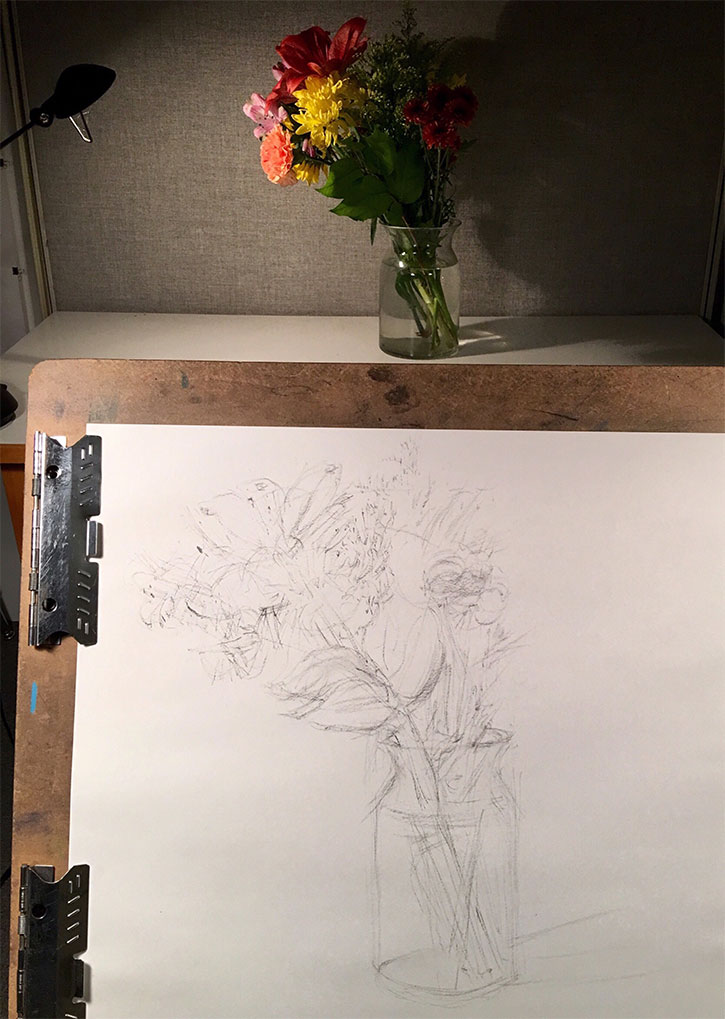

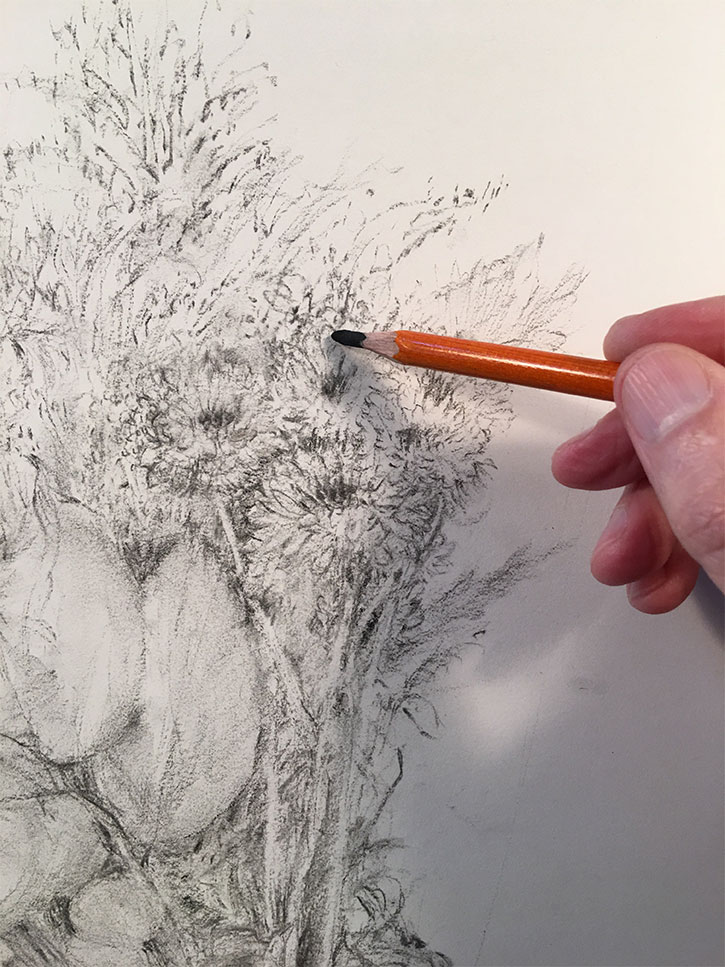

After a full day’s work, I finally sat down that night to get started. I observed how various masses comprising the bouquet leaned mostly to the left. The dominant angles of the stems dictated how my first gestural charcoal lines would be laid on the paper (shown above).

The purpose of lightly drawn block-in lines and shapes is to capture the action and position of dominant masses. These initial lines and shapes are the most important measurements in the drawing. They map out an abstract framework for navigating the rest of the composition.

My initial curiosity with the curved carnation stem and dancing tree leaves remained the thrust of my composition. Several loosely sketched construction lines depicted the tilt of weight-bearing stems in the vase. I liked how these lines suggested movement and created an unbalanced tension.

The evening was going well as I bounced around the entire page, sketching and comparing. John Berger describes the process eloquently: “My task now was to co-ordinate and measure: not to measure by inches as one might measure an ounce of sultanas by counting them, but to measure by rhythm, mass and displacement; to gauge distances and angles as a bird flying through a trellis of branches; to visualize the ground plan like an architect; to feel the pressure of my lines and scribbles towards the uttermost surface of the paper, as a sailor feels the slackness or tautness of his sail in order to tack close or far from the surface of the wind.”

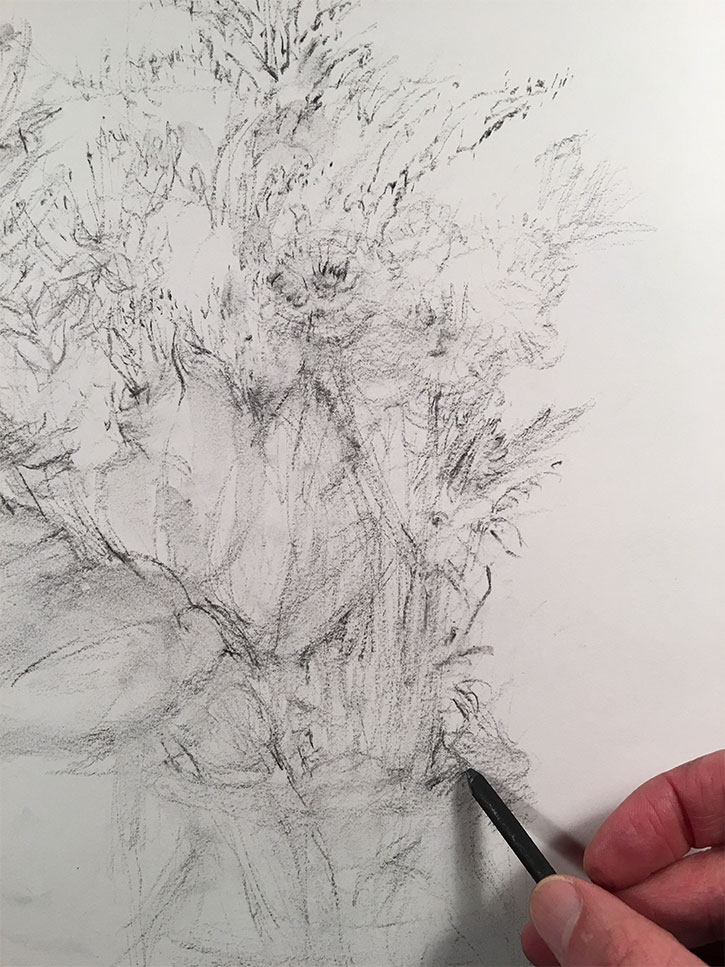

But as the evening pressed on, frustration began to show in my charcoal strokes. Sketching deeper into my subject, I sensed there were inaccuracies somewhere in the core framework. I became lost in a torrent of tangled lines in search of errant measurements.

The frustration mounted as I was trying to swim upstream. I was getting in over my head. This was the pivotal moment in the drawing—when it can either fall apart or fall together—when I tell my students to step back from the work, breathe deep, and look at the whole composition. And this is when I finally spotted the problem!

The distance from the bottom left of the vase to the carnation at the far left was too short. Instead of erasing, I used a cloth to lighten the charcoal lines depicting the masses of leaves and areas around the carnation. I then drew an angled line from the bottom left of the vase to the carnation (still visible, as shown above) to measure the large negative shape to the left of the vase. Then I focused on carefully sketching through my mistakes, adding layers of corrected lines and shapes.

Drawing is action and reaction. Berger wouldn’t have skipped a beat while correcting these mistakes. “One now begins to draw according to the demands, the needs, of the drawing. If the drawing is already in some small way true, then these demands will probably correspond to what one might still discover by actual searching. If the drawing is basically false, they will accentuate its wrongness.”

After making crucial adjustments in the composition, the creative momentum shifted and I was back in the flow. At night’s end, I moved beyond the abstract framework and an accurate likeness of the subject began to emerge. I still hadn’t drawn specific details, but fatigue was getting the best of me. It would be best to look at the composition with fresh eyes in the morning.

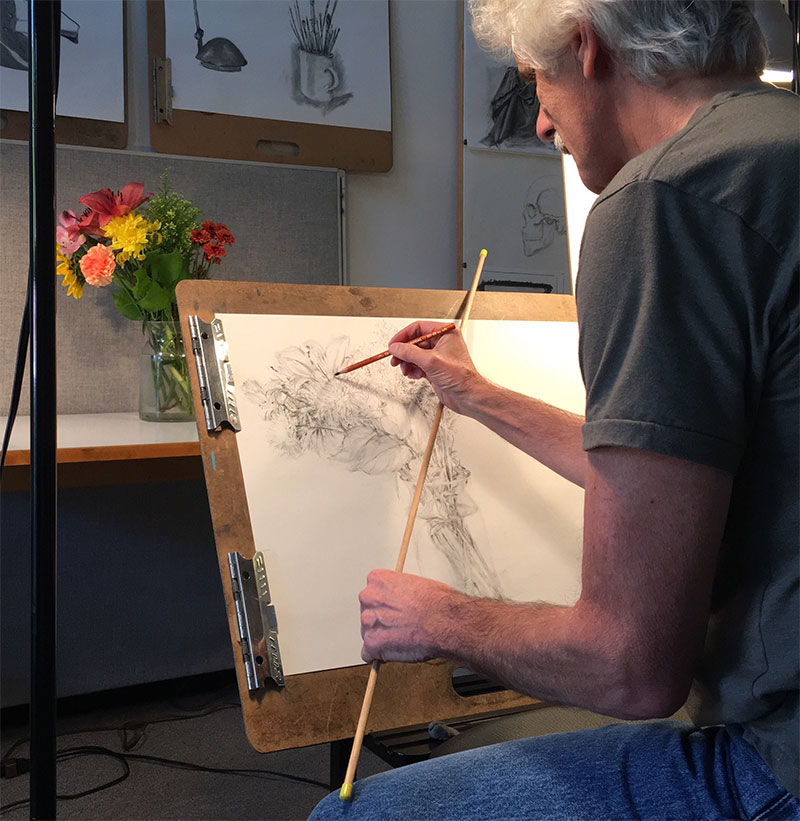

The excitement of continuing my drawing got me out of bed early. The big changes in measurements I had done the night before held true. Feeling energized, I knew I was beyond mid-stream in the process and entered the final stage where the truest joy of drawing takes place.

Relieved that several hours of correcting my block-in measurements and sketched contours were behind me, I settled in and started drawing details and washing in tonal values. My charcoal strokes began to emphasize the natural movement of flowers, stems, and branches succumbing to the pull of gravity.

Berger and I were now on the same page. “In some places I could clearly see that a passage was clumsy and needed checking; in others, I allowed my pencil to hover around—rather like the stick of a water-diviner. One form would pull, forcing the pencil to make a scribble of tone which could re-emphasize its recession; another would jab the pencil into re-stressing a line which could bring it further forward.” I was effortlessly making my way to the sweetest part of the process—finishing!

I had pushed through the river that is the process of drawing. By trusting my first block-in lines, stepping back to assess the entire composition, and sketching through mistakes, I was able to put the river behind me. Berger reminds us that “a line, an area of tone, is not really important because it records what you have seen, but because of what it will lead you on to see.” I’m now ready to move on and wade into the next unexpected subject that captures my attention.

Ready to cross the river of drawing? Get Started

Info about the book Berger on Drawing.

Rob Court

Latest posts by Rob Court (see all)

- Drawing With Friends - April 11, 2022

- Frozen in Time: Cellphone Users as Models to Draw - April 8, 2022

- Getting Out & Getting Real - June 20, 2021

- Life Lines: Sketching the Unseen World of Movement - June 20, 2021

- The Ups & Downs of Urban Sketching - May 9, 2021