Not even for a brief moment does life hold still for you.

When sketching outdoors, the first lines placed on the page are the most important. These spontaneous marks are what I call life lines and they are vital in translating your first visual reaction to your subject onto paper.

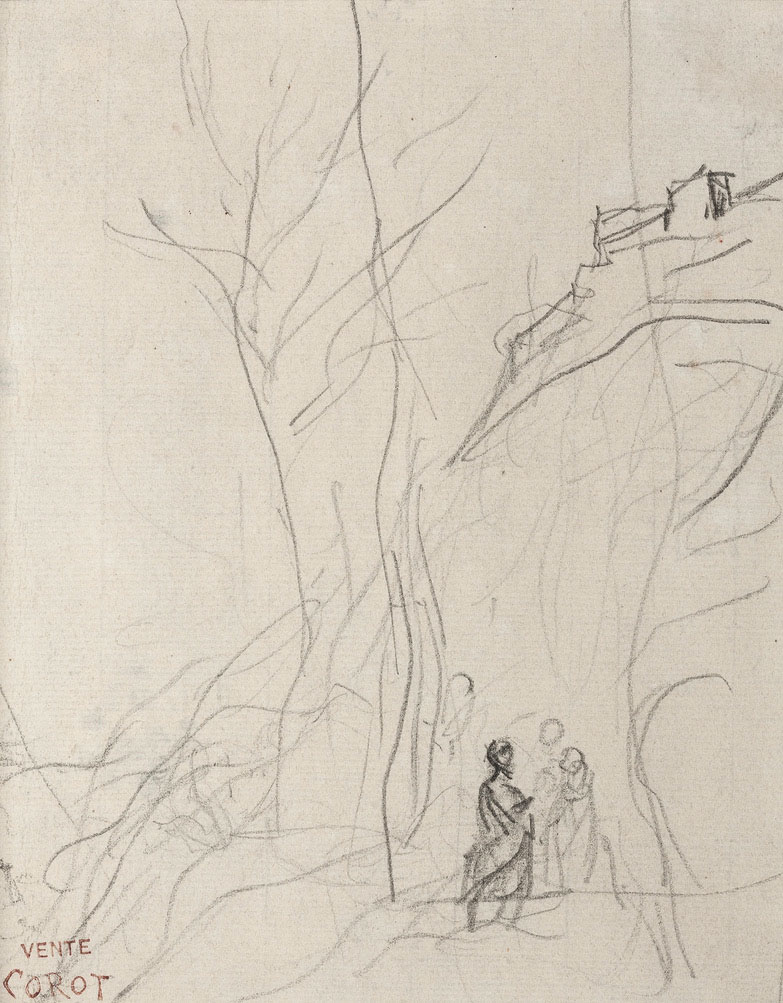

The landscape sketches of master artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) are excellent examples on how to put life lines to work while facing the challenges of observational drawing.

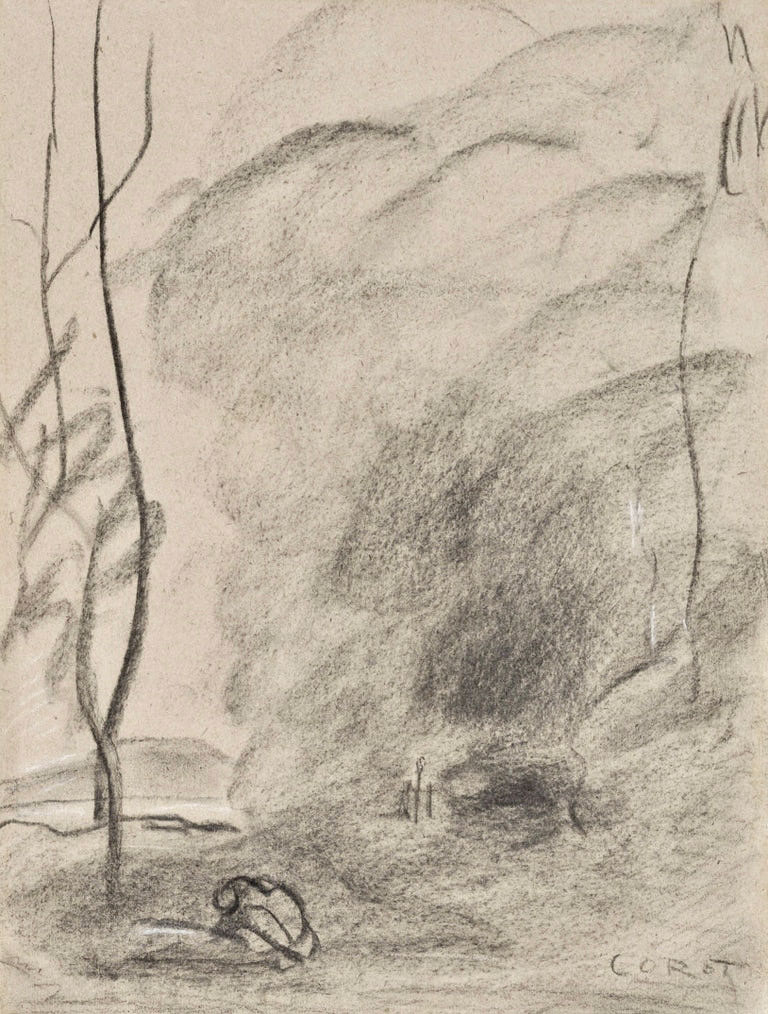

You get a sense of the underlying life lines Corot used to set the tone for his landscape study at Mortefontaine, France (shown above) in 1864. His layering of darker strokes emphasizes the movement of trees growing toward the sun and their lifelong struggle against prevailing winds.

Life lines draw the connection between your mind’s eye and your drawing hand. They are impulsive marks on paper that unveil a world of movement and structure that you actually don’t see.

Drawing What We Don’t See

Corot’s masterful life lines reveal the essence of what we don’t see when drawing from observation: the invisible, abstract framework underneath the surface of all things in our field of vision. Corot’s study sketch of an Italian landscape (shown above) perfectly illustrates my notion of life lines.

His sketch stands on its own as a beautiful piece of art. But Corot’s lightly drawn abstraction serves a direct purpose—laying bare his intuitive visualization of structural elements at the core of towering trees, distant buildings, and figures standing in the foreground. Even the movement—over millions of years—of an imposing cliff is recorded.

Take a moment to study Corot’s sketch. Open your mind’s eye to the immediacy of his well placed, rhythmic life lines. Your imagination starts to fill in the spaces of his abstract framework. A finished landscape painting begins to emerge from the beautiful entanglement of lines.

There is no turning back. Your brain has made the leap from noticing a few abstract marks to visualizing a finished, detailed composition. You have discovered the secret to sketching an unseen world of movement. Your approach to drawing will be radically transformed. Minimal line work becomes bliss and abstraction becomes realism.

Life lines can save you from frustration when sketching complex subjects. They can lead you to the focal point of your composition. A lone figure walks in an Italian countryside, suggested by what are known as action lines.

Practice drawing what you don’t see. Practice drawing with all of your senses. Paint with your pencil, charcoal, or ink. To me, life lines and blocking in the abstract framework are one of the coolest foundational aspects of drawing. All drawings, even the most realistic and detailed ones, are abstractions.

Abstraction leads to realism. Corot was a master at composition. Follow his lead. Try sketching an entire scene with wild abandon—without even lifting your pencil point from the page. Find joy in simplifying complexity.

The initial life lines and abstract framework hold true. Diligence. Stroke by stroke, layer by layer Corot’s watercolor study fills the page. Rhythm, harmony, composition—few ever have mastered the elements of visual art as he did. His music will teach your eye to dance.

And where did this great master’s prowess to visualize and sketch the unseen world of movement take him?…

Ville d’Avray, by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot ca. 1867, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Can you see his life lines?

Rob Court

Latest posts by Rob Court (see all)

- Drawing With Friends - April 11, 2022

- Frozen in Time: Cellphone Users as Models to Draw - April 8, 2022

- Getting Out & Getting Real - June 20, 2021

- Life Lines: Sketching the Unseen World of Movement - June 20, 2021

- The Ups & Downs of Urban Sketching - May 9, 2021